[Originally published at http://excalculus.tumblr.com/post/71595885559/meet-the-icefish on December 29, 2013. Edited December 15, 2018. All images link to their original sources.]

I have free time, and that means more biology! Today’s creature is one I’ve been meaning to write about for a while: the crocodile icefish, Pagetopsis macropterus.

The name seems pretty self-explanatory – crocodile for the long, flat, toothy snout, and icefish because it lives exclusively in the frigid waters just off the coast of Antarctica. But there’s something very strange going on with this fish, one of the symptoms of which can be seen just by looking closely: it’s ghostly pale, almost transparent. Its internal organs are visible through its body wall, and some of its skeletal structure is faintly visible.

Now, transparency in fish is unusual but not unheard of. Generally this is due to a combination of small size and lack of skin pigment, as in some small aquarium fishes. But despite being scaleless the icefish has markings, so it’s not a pigmentation issue. For a clue as to what’s going on, look back at the first picture. Specifically, look at the gill covers. On a fish this transparent you should be able to see the gills clearly, right? Anyone who has ever bought whole fish at a market now knows there is something odd afoot, for the gills of a healthy live or recently dead fish are bright red with oxygenated blood. Stale fish have a brownish purple color. Icefish?

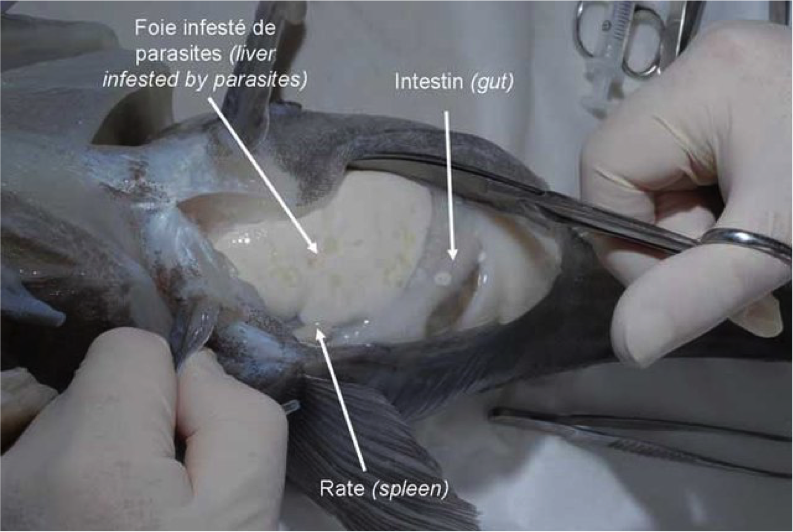

Completely and utterly white. That’s bizarre enough, but things get really strange when you cut one open.

For anyone who has never seen the inside of a normal fish, a comparison:

Internal organs should not be white, but the icefish seems to be doing just fine. Something has changed, something that normally gives flesh, viscera and fish gills color and opacity. The gills are actually the best clue here, as they are essentially made of blood vessels in order to extract oxygen from the water. Let’s compare icefish blood to that of a close relative:

And there’s your answer. Icefish blood looks more like water than blood, because the icefish is unique among vertebrates for lacking red blood cells. That’s incredible enough for a closer look, so genes were sequenced and it was found that the key change here was a deletion in the genes that code for the oxygen-carrying protein hemoglobin.

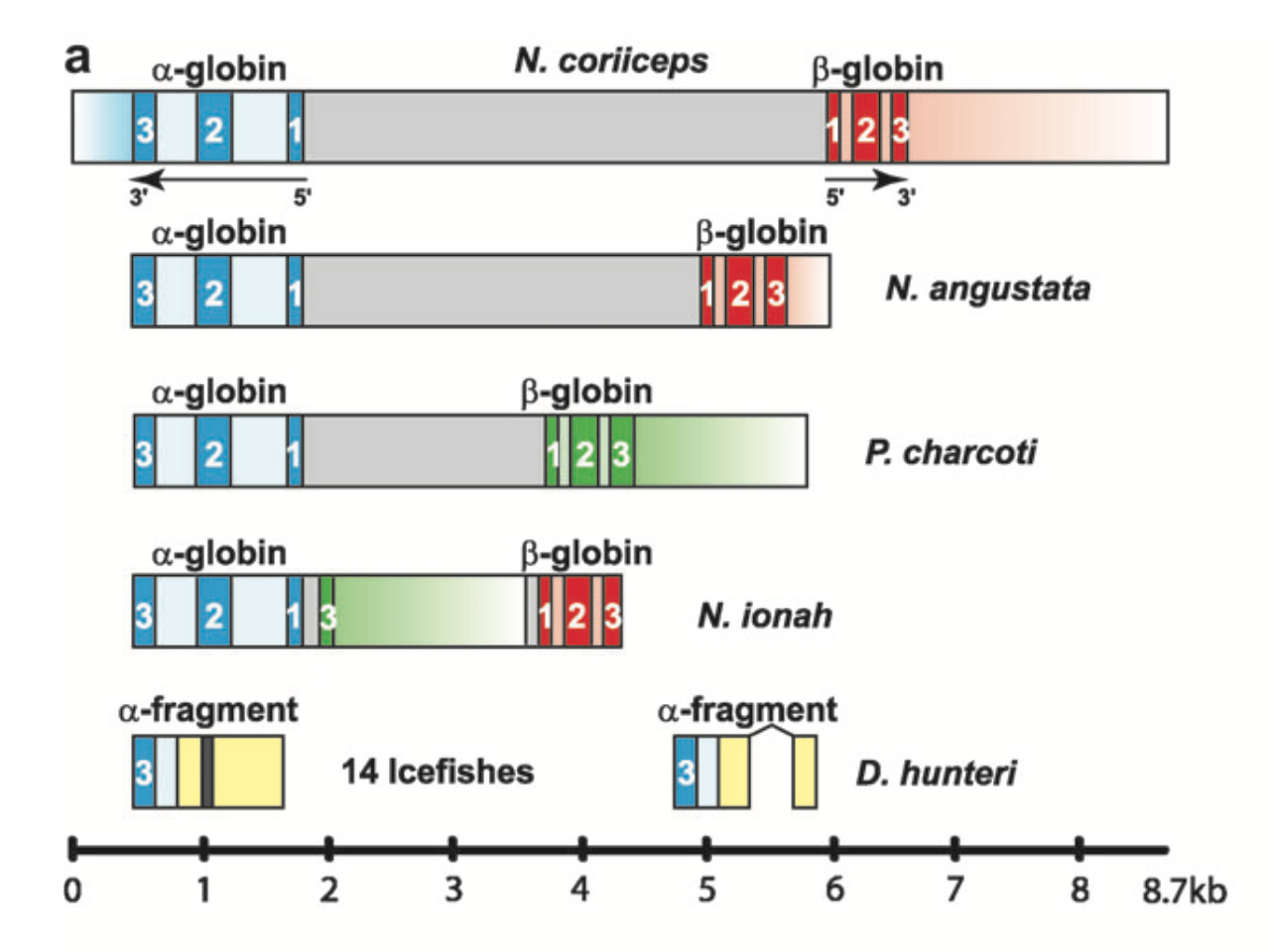

Hemoglobin has an alpha chain and a beta chain. Sequencing the DNA of many icefish species and several relatives reveals that icefishes retain part of the alpha chain sequence, but the beta chain is missing entirely or remains as scrambled fragments. (Near et al. 2006) This genetic fossil tells us that the ancestors of the icefish had normal hemoglobin genes, but managed to lose them.

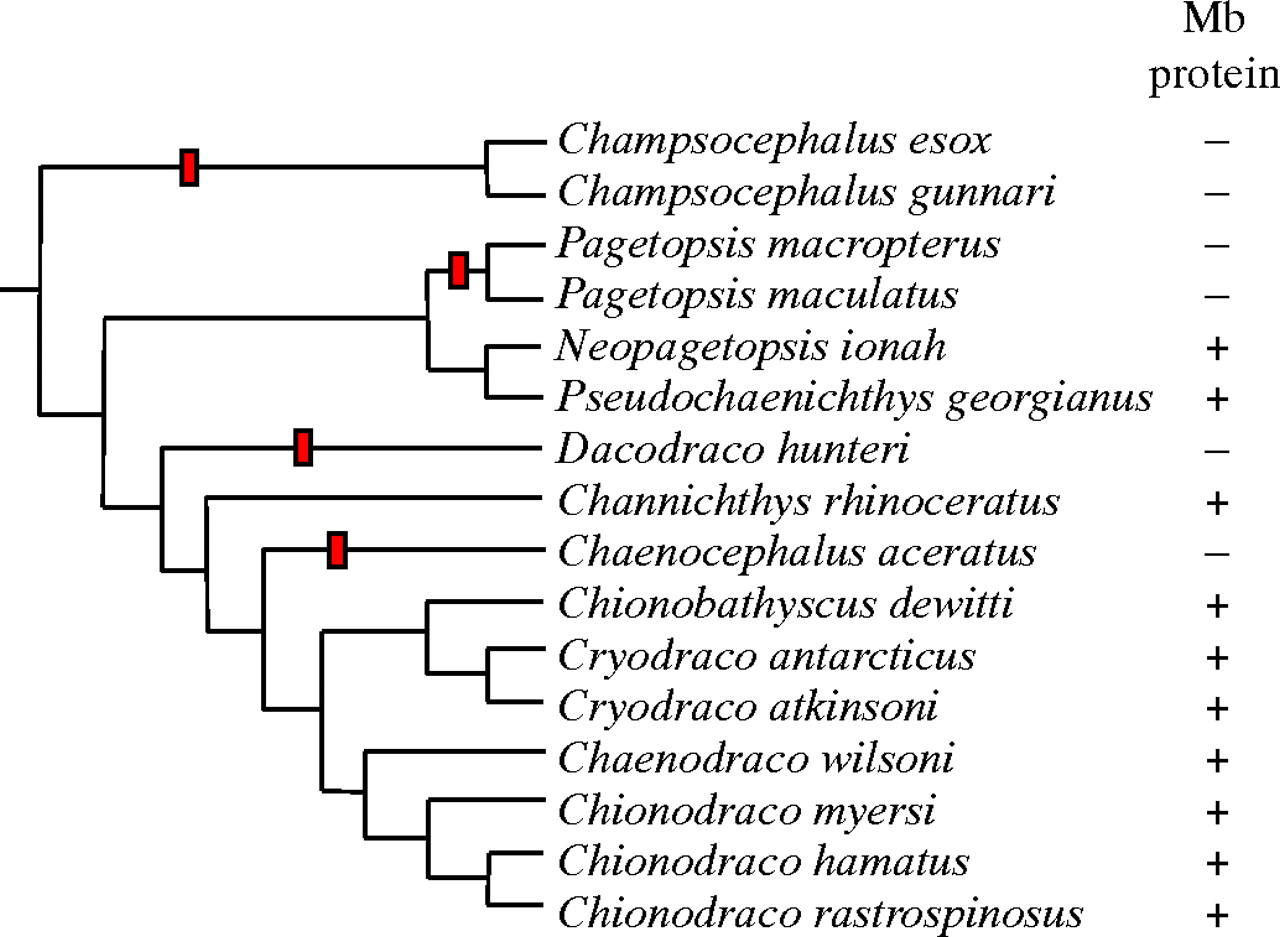

So now we know why icefish have clear blood, but how on Earth did this one make it out of quality control? Hemoglobin is… somewhat important. It’s how oxygen gets from lungs or gills to the rest of the body. Every other vertebrate relies on hemoglobin to survive. And if you thought the malarkey stopped there, you thought wrong: On top of this, there have been not one, but several distinct mutation events in which icefishes lost myoglobin as well. (Myoglobin is an oxygen-binding protein found in vertebrate muscle. This is what makes muscle red.)

The fact that the icefish still exists suggests that flinging your oxygen-binding proteins out the window either does not affect survival or confers an advantage, which seems blatantly untrue.

One theory is that as counterproductive as it looks, this may actually be an adaptation to the icefish’s habitat. Antarctica is, to use a highly technical term, balls cold. The water it lives in is about at the freezing point of even seawater. This is so cold that the entire larger family that icefish belong to have evolved blood proteins that function as antifreeze in order to function in an environment that is simply too cold for most fish to survive. (The antifreeze proteins are another interesting case – analysis reveals that they developed from pancreatic digestive enzymes.) Liquids become more viscous as they cool, and normal blood is already thick, sticky stuff. At sub-zero temperatures it becomes very difficult to pump through an animal’s body. By removing red blood cells the icefish makes its blood much thinner and easier to pump, meaning there might be a selective advantage in freezing but nutrient-rich waters.

There’s one glaring problem, though: by every scientific measure, losing hemoglobin and myoglobin has no benefit. (Sidell and O’Brien, 2006) Let’s go through the data.

- Icefish lacking hemoglobin have massive heart sizes and blood volumes compared to their red-blooded relatives from the same environment. Calculating cardiac energy consumption based on heart size and blood pressure shows that they expend about twice as much energy pumping blood as a fish with red blood cells.

- Icefish have much denser capillary beds than their relatives. This reduces the distance oxygen has to diffuse to get to a given area of tissue, suggesting that there isn’t exactly an abundance of oxygen to work with.

- When icefish hearts are isolated and their function measured, hearts from species lacking myoglobin perform significantly worse than those from species that have myoglobin. When myoglobin function is blocked the myoglobin-negative hearts are unaffected, but the myoglobin-positive hearts lose so much function that they are actually worse off. The fact that the myoglobin-negative hearts come out ahead in this situation means they have performance adaptations specifically to compensate for lack of myoglobin.

That last item is positively damning. If you have to put so much effort into adapting to your “adaptation,” it’s likely not an adaptation at all. All this points to the fact that the hemoglobin and myoglobin deletions were in fact bugs that the species managed to survive rather than features that made them more fit. (I beg you to read the paper – it’s got some very neat pictures of hearts and capillaries, a lot of great information, and it’s titled “When bad things happen to good fish.”)

The fact that they live in Antarctica in the first place is likely the only reason they got away with it: Cold water has several interesting properties, one of which is an increased ability to dissolve gases. As a matter of fact, the waters of the Antarctic are effectively saturated with oxygen. Combined with scaleless skin for better absorption, an overpowered heart, and a spectacularly dense capillary network, it’s possible for a vertebrate to get enough oxygen using what is essentially an insect-style open circulatory system.

So there you have it: a fish so hardcore that it bleeds antifreeze and survived deleting all its oxygen-carrying proteins.

- Thomas J. Near, Sandra K. Parker, H. William Detrich; A Genomic Fossil Reveals Key Steps in Hemoglobin Loss by the Antarctic Icefishes, Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 23, Issue 11, 1 November 2006, Pages 2008–2016, https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msl071

- Sidell, Bruce D., and Kristin M. O’Brien. “When bad things happen to good fish: the loss of hemoglobin and myoglobin expression in Antarctic icefishes.” Journal of Experimental Biology 209.10 (2006): 1791-1802.